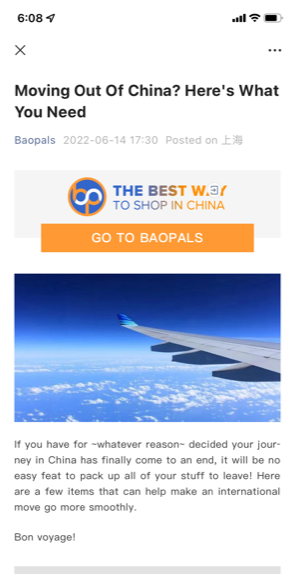

I’m in quarantine!

Not American-style quarantine where we were all, “I’m quarantining except when I stop by Target for a few essentials.” Real quarantine, where cameras make sure I don’t leave my room, meals are left outside my hotel room three times a day, I have to report my temperature twice a day and get tested for Covid every few days, and I don’t actually see people at all, except when someone in full PPE comes to stick swabs up my nose and down my throat.

All my meals include fresh fruit, which is sometimes not entirely recognizable but nonetheless appreciated!

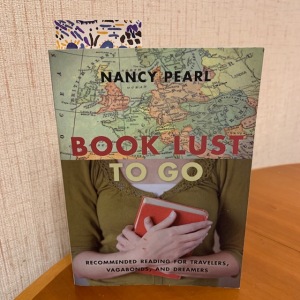

To keep myself busy, I thought I’d do a blog post that was long in my mind during my time in Kazakhstan when I found that books about the Soviet ‘stans, at least in English, weren’t easy to come by. Even super librarian Nancy Pearl wasn’t much help.

The combined number of books about Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan in Nancy Pearl’s travel book? ZERO.

So with all this time on my hands, I can document the results of my reading efforts in case any random internet user is ever looking for (mostly) non-academic books about Soviet Central Asia. Feel free to skip this post if you’re not interested in reading about me, reading about Central Asia. Hopefully my next post will be post-quarantine, full of interesting tidbits about my new home.

Apples Are From Kazakhstan by Christopher Robbins: A pretty breezy travelogue until midway through when the author gains tremendous access to (now former) president Nursultan Nazarbayev and, seemingly because of that, forms an awfully rosy view of him. So it’s about Kazakhstan but also a lesson about the perils of access journalism (Hello Maggie Haberman)?

Letters from Between the Humps: Adventures and Misadventures in Kazakhstan by Patricia Vail: self-published memoir by an American lawyer volunteering in Almaty when Kazakhstan was newly independent. I enjoyed the picture of 1990s Almaty. Some things I recognized as 100% “my” Almaty while other things were completely different.

Lands of Lost Borders: A Journey on the Silk Road by Kate Harris: Authored by an over-achieving academic, scientist, adventure traveler, and writer. Perhaps not the best read for anyone prone to an inferiority complex. Kazakhstan is only a small part of the overall journey but it was still a good read.

A Thousand Sisters: The Heroic Airwomen of the Soviet Union in World War II by Elizabeth Wein:  Young Adult non-fiction, includes only a tiny morsel about Kazakhstan: one of the “Night Witches” who flew in combat against the Nazis was Khiuaz Dospanova, a Kazakh who fought for the USSR as a pilot, navigator, and gunner.

Young Adult non-fiction, includes only a tiny morsel about Kazakhstan: one of the “Night Witches” who flew in combat against the Nazis was Khiuaz Dospanova, a Kazakh who fought for the USSR as a pilot, navigator, and gunner.

The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan by Sarah Cameron: The Ukrainians lost between 3 and 7.5 million of their population during the Holodomor, the famine of 1932-33. The Kazakhs “only” lost 1.5 to 2.3 million. But as a percentage of population, the Kazakh famine, in which 38% of Kazakhs died, killed the greatest percentage of one specific ethnicity. Scholars debate whether these famines qualify as genocide or just incompetence. Ms. Cameron seems to come down mostly on the side of incompetence coupled with Russian ignorance about the environment and culture in Kazakhstan. An academic read but not too taxing.

Bas-Relief from the Kazakhstan Pavilion at VDNKh Park in Moscow. It’s supposed to be happy Kazakh herders but I couldn’t help but think “driving their cattle to slaughter in order to feed the Russians while the Kazakhs starve to death…”

Dark Shadows: Inside the Secret World of Kazakhstan by Joanna Lillis: Lillis is an English language journalist who lives in and covers Kazakhstan. Her book was published about five months before Nazarybayev resigned and she paints a far less favorable picture of him than does the author of Apples Are From Kazakhstan. I assume these short essays were adapted from her newspaper and magazine writings. Good for short bursts rather than in-depth examination. Want to learn about the famine but don’t want to read an entire book? Joanna Lillis has a chapter for you.

The Great Game: Struggle for Empire in Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk: The definitive English language book on 19th century Russian and British maneuverings in Central Asia when the British were very concerned that Russians were setting up shop in the region specifically with an eye to closing in on and ultimately challenging British rule in India. It’s a pretty deep dive into the topic and I admit that I didn’t always follow all of the military maneuverings.

Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World by Justin Marozzi: Tamerlane/Timur is more Uzbekistan’s man than Kazakhstan’s but he did build Kazakhstan’s best known historic sight and he also died in what is now Kazakhstan. I get that when you spend years researching and writing such a book, you come to feel for your subject and maybe don’t want him to come off as a total douchebag. But I thought Marozzi was maybe too fair to Gurgin Timur.

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World by David Anthony: The steppe discussed here tends to be more Ukrainian and less Kazakh but modern Kazakhstan’s territory does make some appearances and if you are interested in the development of any of the title topics, there’s a lot of fascinating information. I found the language parts especially engrossing.

At Home on the Kazakh Steppe: A Peace Corps Memoir by Janet Givens: The writer spends much of the book very disappointed in her husband/fellow volunteer, who sounds like a tee-totaling stick in the mud who won’t even pay for his portion of a meal if alcohol is served at it. Dude.

Chasing the Sea by Tom Bissell: Former Peace Corps Volunteer (of a whole six months) returns to his country of service, Uzbekistan. I first read this in 2016 after having read a devastating article about the Aral Sea by Bissell in Harper’s. I didn’t love this book, in part because he hardly spends any time at the Aral itself. I re-read it in 2019 around the time I traveled to Uzbekistan and while I still didn’t love it (Bissell has a certain sad sack quality I don’t take to), it was better the second time around when I was more interested in reading about Uzbekistan in general and not the Aral in particular.

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World by Peter Frankopan: Maybe not quite as ground breaking as the author thinks it is (and The Guardian points out some errors), but it’s a worthy effort to look at world history centered more on silk road trading routes (Persia, Central Asia, China) and less on the Mediterranean (Egypt, Greece, Rome).

The Lonely Yurt by Smagul Yelubay: Not easy to track down or to read. This is a fictionalized story of Kazakhstan’s great hunger, mentioned above. The English translation seems to be the work of a nonprofit association and I don’t know if it’s the translation or the original that is so choppy. Some editing choices around page layout and spacing makes it even more so. If you can get through it, there’s worthwhile description of life in the auls (nomadic settlements) in the early years of Soviet rule, and some heartbreaking scenes of starvation as the famine takes hold.

The Travels of Ibn Battutah by Ibn Battutah edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith: The medieval Moroccan-Berber traveler visited Central Asia in the 14th century. His memoirs are crazy long and the most accessible English language version is severely edited. So do I blame the author or editor for the fact that Afghanistan and Turkestan combined get covered in about 10 pages? Not a super big fan of the titular hero as he takes slaves, pearl-clutches when he encounters unveiled women and platonic friendships among the sexes, and seems a-okay with some pretty horrifying customs (woman caught in adultery? Rape her to death!).

The Dead Wander in the Desert by Rollan Seisenbayev: Amazon is a legit terrible company but the translation arm of their business brings some pretty obscure works into the English speaking world and for that it’s hard not to be grateful. This sprawling epic sees characters go from WWII, through the Soviet-Afghan wars, through one of Kazakhstan’s most famous protests, almost up to Kazakh independence. The main characters are a Kazakh father and son straining against Soviet mismanagement of the Aral Sea.

Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World by Jack Weatherford: Minnesota connection! A professor at Macalester is out to make a hero of Genghis Khan, or at least to balance his legacy, and damned if he doesn’t make a pretty convincing case of it. Better than Justin Marozzi did with Timur. I didn’t realize at first that the book is about the Khan’s entire legacy, not just his life, so I was surprised when Genghis died mid-way through the narrative.

Open Mic Night in Moscow: And Other Stories from My Search for Black Markets, Soviet Architecture, and Emotionally Unavailable Russian Men by Audrey Murray: You wouldn’t guess it from the title but this travelogue starts in Almaty and continues through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan for the first full half of the book. Whether you enjoy it will depend heavily on whether you find the author amusing. I personally vacillated between being impressed with and annoyed by her. Annoyed when she veered towards ugly American stereotypes, impressed when she navigated the labyrinth of visa bureaucracy without help from locals on staff at the consulate like I did!

A Carpet Ride to Khiva by Christopher Aslan Alexander: I bought my own carpet in Bukhara, not Khiva, and I bought wool, not silk. After reading this I was ready to go back to Uzbekistan to throw down another few thousand dollars for a silk Khivan rug. The narrative can get a little bogged down in the details but it really makes you appreciate all the work that goes into your souvenir.

Sovietistan: Travels in Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan by Erika Fatland: enjoyable travelogue, although I did find an error or two. Lots of local color and even hard-to-explore Turkmenistan gets a section. That said, despite it’s heft, it is still trying to cover five whole countries in one book, so it sometimes goes wide but not deep.

Murder in Samarkand (published in the US as Dirty Diplomacy) by Craig Murray: the memoirs of a British ambassador who is definitely a dick but who also stood up to his own government when they were hell bent on licking the boots of George W. Bush. Lots of minutiae of foreign service life and way too much about the ambassador’s alcohol fueled extracurricular activities involving exploitative sex with a local woman half his age.

Turkestan Solo: A Journey Through Central Asia by Ella Maillart: A Swiss lady traveler, in the early years of the Soviet Union, starts in Moscow before heading to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan for mountain climbing, and then Uzbekistan for more familiar (to me) sightseeing. At the end when she is at the Aral Sea it’s hard not to feel sad about all that’s been lost there.

A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and The Creation of the Modern Middle East: by David Fromkin: Accidental Central Asia book! I read this account of how the winners of WWI cut up the remains of the Ottoman empire and while most of the focus is indeed on the middle east, several key decisions involve the Turkic speaking parts of the world under Russian control, aka Central Asia. Spoiler alert: judging by recent events in the middle east, the western powers did not learn anything.

A Ride To Khiva: Travels And Adventures In Central Asia by Frederick Burnaby: A “great game” era classic as Burnaby, Victorian-era British army intelligence officer, makes his way to Khiva, often skirting official Russian rules to do so.

Red Sands by Caroline Eden: Part cookbook, part travelogue. It came out while I was in Chinese class, lacking both free time and a well-equipped kitchen, so I have yet to try any of the recipes. But it’s a very beautiful book to look at. There’s also a suggested reading section that is super helpful. The same author co-wrote another recipe + essay book, Samarkand – Recipes and Stories from Central Asia and the Caucasus, that is a bit more of a straight up cookbook.

A Shadow Intelligence by Oliver Harris: To redeem Nancy Pearl…I did a pre-departure scroll through her Twitter feed to get ideas for fun quarantine reads that I could immediately check out of the library. This British spy thriller takes place in Kazakhstan and doesn’t come across as written by someone who has never been there. Impressive! Although, as with many spy thrillers, it’s awfully hard to keep track of who the bad guy is.

I still have a few books about Central Asia that are on my “to-read” list:

- The Silent Steppe: the story of a Kazakh Nomad under Stalin by Mukhamet Shayakhmetov

- In the Kirghiz Steppes by John W. Wardell

- Mission to Tashkent by F.M. Bailey

- Through Khiva to Golden Samarkand by Ella Robertson Christie

But I don’t know when/if I will get to them. China has crept into my reading interests and lord knows books about China aren’t hard to track down, no matter if you want history, politics, literary fiction, or mystery and adventure novels. But I chose Kazakhstan, whereas China was chosen for me so maybe I will never be as excited about reading Chinese books as Central Asian books. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Here is where I stop to acknowledge the many valid concerns about forced or sweatshop labor in China. And yet, an interesting development in the bag industry: China’s labor is already a bit too expensive for some western retailers. To compete, our guide/factory owner has opened factories in neighboring Myanmar, where labor is cheaper. Much of what they do here in China is now limited to purchasing materials, creating samples, and then shipping those across the border for mass production.

Here is where I stop to acknowledge the many valid concerns about forced or sweatshop labor in China. And yet, an interesting development in the bag industry: China’s labor is already a bit too expensive for some western retailers. To compete, our guide/factory owner has opened factories in neighboring Myanmar, where labor is cheaper. Much of what they do here in China is now limited to purchasing materials, creating samples, and then shipping those across the border for mass production.

Anxious to make use of the free time, I chose a tour of China’s wine country, Ningxia. Yes, there’s wine country in China, although it doesn’t attract the tourists of Napa Valley. Or even

Anxious to make use of the free time, I chose a tour of China’s wine country, Ningxia. Yes, there’s wine country in China, although it doesn’t attract the tourists of Napa Valley. Or even

I just turned on my air conditioning. On March 18. Supposedly it might get colder next week but I’d been fighting against the March heat (!) for over a week and I couldn’t do it anymore. I need to be comfortable in my house because I’m always here. I’ve spent the last few months practically in hibernation.

I just turned on my air conditioning. On March 18. Supposedly it might get colder next week but I’d been fighting against the March heat (!) for over a week and I couldn’t do it anymore. I need to be comfortable in my house because I’m always here. I’ve spent the last few months practically in hibernation.

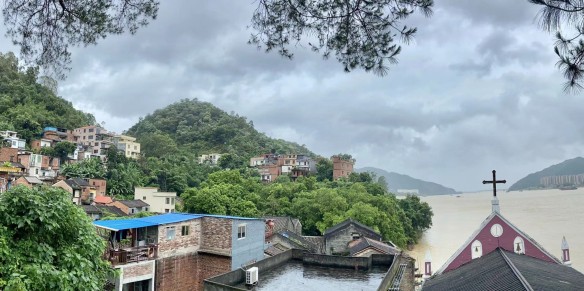

It’s filled with many buildings in classic Lingnan (Cantonese) architectural style but its only real claim to fame is that Mao’s English language translator lived here.

It’s filled with many buildings in classic Lingnan (Cantonese) architectural style but its only real claim to fame is that Mao’s English language translator lived here.

A former guard tower has been turned into a cool museum chronicling Guangzhou’s history.

A former guard tower has been turned into a cool museum chronicling Guangzhou’s history. The park also contains what used to be the symbol of Guangzhou, the Five Rams Statue, based on a local legend of a terrible famine, broken only when five gods rode five goats down from heaven and bestowed food (and the goats?) upon the starving populace. These days the Canton Tower has taken over as the most recognizable Guangzhou landmark but old-timers know this one.

The park also contains what used to be the symbol of Guangzhou, the Five Rams Statue, based on a local legend of a terrible famine, broken only when five gods rode five goats down from heaven and bestowed food (and the goats?) upon the starving populace. These days the Canton Tower has taken over as the most recognizable Guangzhou landmark but old-timers know this one.